Authors: Kirsi Immonen, Anna Leinonen & Katri Valkokari VTT

To foster a more sustainable and resilient plastics ecosystem, the ValueBioMat project defined three transformation pathways to describe the necessary transformation from the current plastic system towards the desired target state. Our previous blog post entitled Evolution of problem framing: How to enhance transition towards sustainable plastics? – ValueBioMat explores the story of collective meaning-making processes, during which we formulated these three pathways.

Presently, the plastics system is marked by a linear approach to production and consumption leading to substantial leakage of plastic waste into the environment and fossil-based CO2 emissions due to plastic energy use in the end of life. The current system is heavily reliant on fossil-based raw-materials and trajectory of increasing production and consumption. The desired transformation aims to decrease reliance on fossil raw materials by adopting sustainable alternatives and eliminate the plastic waste problem through effective waste management and recycling strategies. An important goal is to reduce linear production and consumption by promoting circular economy principles.

Each of the identified pathways follows a different logic in the pursuit of sustainability. The first pathway is based on reducing the fossil raw material base by developing new bio-based materials. The second path aims for sustainability by enhancing material circularity, and the third one is based on the goal of reducing plastics consumption. The contents of the three pathways are outlined below.

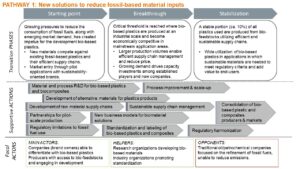

Pathway 1: New solutions to reduce fossil-based material inputs

The first pathway focuses on reducing fossil-based inputs with innovative materials. At the stabilization phase, a 10% share of bio-based material input was jointly noted as indication of such “stabilization.” Starting at less than 2%, the targets exceed this threshold, for instance SYSTEMIQ-ReShapingPlastics-April2022.pdf mentions 20 – 30 % share of biobased inputs until 2050.

Figure 1. PATHWAY 1: New solutions to reduce fossil-based material inputs

The main bottlenecks in increasing bio-based material inputs in plastic value chains are still the material performance and price. The extensive supply chains of fossil-based plastics have several layers, volumes are enormous and fossil-based plastics have multiple variations with performance tailored to be suitable for specific products and their production technologies. These circumstances make it hard for novel bio-based materials and their producers to compete and come to the markets. The novel producers often have limited resources, even the raw material sources may limit the volume. As smaller players, the producers of novel biobased materials have the challenge to identify the plastic products to which their material innovations are suitable and then convince the end product brands on their capacity to provide stable flow of raw materials. Additionally, many bio-based plastic solutions are currently in the laboratory- or pilot phase, and significant efforts to scale up production are necessary to ensure their availability.

Increasing the share of bio-based plastics requires restructuring current supply chains, where traditional petrochemical companies hold strong positions. However, new EU communications on Sustainable Carbon Cycles [1] and Biobased, Biodegradable and Compostable Plastics [2] are driving change and facilitating the transition towards consolidated markets and supply chains for bio-based plastics and composites and are supporting the European Bioecomy Strategy [3]. Standardization and labelling are highlighted as important measures of support in bio-based transition.

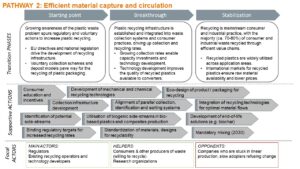

Pathway 2: Efficient material capture and circulation

The second pathway outlines various methods for material capture and circulation. The carbon dioxide capture and circulation of materials, including side-stream usage between different industrial sectors and value chains, ensure that materials remain within the system and their end-of-life is carefully managed.

Figure 2. PATHWAY 2: Efficient material capture and circulation

The barriers to efficient material capture and circulation are similar to those barriers for increasing the share of bio-based plastic use. However, circulation of plastics faces specific challenges with decisions between mechanical and chemical recycling technologies. Mechanical recycling is more cost-effective but produces lower-quality materials, while chemical recycling offers better material properties but is costlier. Both methods face logistics, identification, separation, and material regeneration issues.

Moreover, the availability of material streams for recycling presents a significant challenge for both the expansion of bio-based plastics (pathway one) and the implementation of efficient material circulation. The material stream can be a local industrial side-stream, stream coming from retailer collection or mixed consumer waste and their availability and content varies. Digital marketplaces of materials available for recycling may address some of these challenges. Additionally, combining bio-based, recycled, and fossil materials is a method to gradually increase the proportion of bio-based or recycled raw materials while achieving the desired material properties for example through mass-balance route and ISCC Plus certification [4]. EU Regulation and Directives focused on various application areas are containing targets for reuse and recycling and for example latest Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive [5] contains also mandatory mixing targets for recycled material contents in products.

Pathway 3: Sustainability through reduced plastics consumption

The third pathway focuses on addressing the comprehensive sustainability issues associated with plastics. Various global stakeholders, including the UN International Negotiation Committee (INC), are dedicated to identifying solutions to reduce plastic pollution’s impact on ecosystems and human health. One potential approach is through the reduction of plastic usage. This path presents significant challenges, as evidenced by the outcomes of discussions in Busan at the end of 2024. For more details, see the article Plastic pollution treaty negotiations adjourn in Busan, to resume next year | UN News [6].

Figure 3. PATHWAY 3: Sustainability through reduced plastics consumption

The barriers and drivers of this sustainability through reduced plastics consumption pathway can be divided into two major issues. Consequently, both perspectives could increase transparency of sustainability issues within plastic supply chains and thereby influence also to reduction of plastic consumption.

On the one hand, mission-oriented regulation can replace prohibitive regulation, which acts as a barrier for system transition. Science-based methods for sustainability assessment can support systemic policy analysis and industrial decisions. These novel methods could help brand owners perform broader analyses when selecting plastics for their products. This would facilitate system-level assessment rather than sub-optimization.

On the other hand, the development of product-service solutions could support increasing product life-time or utilization rate. Piloting both new manufacturing technologies and business models based on different R strategies [7] could support behavioral changes of consumers. New Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Directive (ESPR) became effective July 2024 [8]. The ESPR aims to significantly improve the sustainability of products placed on the EU market by improving their circularity, energy performance, recyclability, repairability, and durability. It will also play a central role in developing a strong, well-functioning single market for sustainable products in the EU.

Footnotes:

[1] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/733679/EPRS_BRI(2022)733679_EN.pdf

[2] https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/plastics/biobased-biodegradable-and-compostable-plastics_en

[3] https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/research-area/environment/bioeconomy/bioeconomy-strategy_en

[4] https://www.iscc-system.org/certification/iscc-certification-schemes/iscc-plus/

[5] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/745707/EPRS_BRI(2023)745707_EN.pdf

[6] Plastic pollution treaty negotiations adjourn in Busan, to resume next year | UN News

[7] These are R0 Refuse, R1 Rethink, R2 Reduce, R3 Reuse, R4 Repair, R5 Refurbish, R6 Remanufacture, R7 Repurpose, R8 Recycle and R9 Recover

[8] https://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/standards-tools-and-labels/products-labelling-rules-and-requirements/ecodesign-sustainable-products-regulation_en